Dec 15, 2025

1. European rearmament and threat inflation

Lord Robertson was the lead author of Britain’s Strategic Defence Review, published on 2 June 2024. The Review effectively seeks to implant a war-ready mindset across society, insisting that the UK must be “better prepared for high-intensity, protracted war” and that its war-making, and therefore deterrence, capacity should “permeate every aspect of society.” (See my post of 22 July criticising the SDR.)

At the London Defence Conference Investment Forum in December 2025, Robertson expanded on these themes with an even more alarmist reading of Europe’s strategic position. He identified Russia as the primary and overriding threat to the United Kingdom, arguing that the Kremlin increasingly portrays Britain as a proxy for the United States—a narrative which, in his view, signals that Britain would be among the first targets should Russia succeed in reconstituting its armed forces. For Robertson, this threat justifies a dramatic surge in British defence spending: with American support, the UK must spend around 5% of GDP on defence; without it, 7% might be needed.

Lord Robertson says:

“We need to be very, very worried about how this ends up, because we are under threat as well. It’s quite clear from the Russian press and the Kremlin-controlled media that we, the United Kingdom, are being seen as a proxy for America. It’s inconvenient to attack America on a broad scale because of the relationship between Trump and Putin, so we, the United Kingdom, are in the crosshairs. Relentlessly, the Kremlin media is attacking ‘the Anglos’, ‘the UK’, ‘the English’. So we need to be worried as a country as a whole that if Russia got the space to reconstitute its armed forces—and it’s already doing so—but if it could on a grander scale, then clearly the rest of Europe is in danger. If I lived in Moldova or Armenia or Azerbaijan, I would be very, very worried about the possibility of a deal being done that left Russia with its forces intact and with at least some prize to be gained from Ukraine.”

Yet his presentation of the Russian threat is weird. He presents Russia as economically failing, militarily inept (“advancing one millimetre at a time” in Ukraine), and demographically imploding (“the younger generation being eliminated”), while simultaneously arguing that Russia is an existential threat not just to its neighbours but to Europe as a whole (the UK is “directly in the crosshairs”).

These two claims cannot both be true. A state suffering acute demographic decline, a stalled military, and a failing economy cannot simultaneously constitute a multi-theatre threat to Europe. The case achieves its bare minimum of plausibility by suggesting that the Russian threat against which we have to arm ourselves takes the form of “greyfare” rather than warfare: activities such as cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, sabotage, political meddling, and proxy operations—actions just below the threshold of war, which in fact obliterate the distinction between peace and war. But it is absurd to argue that such threats, which may well exist, justify spending an extra 4% of GDP on “whole-society” defence.

Robertson’s argument is a classical case of threat inflation—or, less politely, paranoia—defined as an unfounded or exaggerated belief that others are hostile, threatening, spying, or plotting against you.

The House of Lords debate of 8 December conveyed the same sense of alarm, with peers across the political parties urging a “whole-society” mobilisation and lamenting the public’s supposed complacency, especially among the young. Speakers insisted that Britain must “wake up to the threat we face” (Lord Coaker) and warned that the country is already under attack “both at home and from abroad” (Lord Robertson). The atmosphere was one of urgency: traditional boundaries between civilian and military spheres were treated as obsolete, with peers calling for steps comparable to those taken in France and Germany to put the UK on “a comparable readiness footing” (Baroness Goldie), and for the Armed Forces to “reconnect with societal attitudes… particularly among young people” (Lord Stirrup). The Minister, Lord Coaker, concluded that the threat is “upon us now, not in a year’s time”—a formula that reflects less a measured assessment of specific risks than a growing political appetite for reshaping society around a permanent sense of insecurity.

2. The Budapest Memorandum

But such paranoia is by no means unique to Robertson. He simply reiterates the Western narrative that Russia is an inherently aggressive power whose authoritarian character makes it incapable of honouring agreements. One piece of evidence repeatedly cited is Moscow’s breach of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, under which Ukraine surrendered the Soviet nuclear warheads on its territory and acceded to the Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear-weapon state in exchange for “security assurances” from Russia, the US, and the UK (with China and France issuing separate unilateral assurances). Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014, and its invasion of Ukraine in 2022, is cited as decisive evidence that no reliance can be placed on Russian assurances. This, in turn, lies behind the dominant European view that Russia must be decisively defeated in Ukraine; otherwise, it will simply use any breathing space to regroup and continue its aggression.

However, this is a one-sided interpretation of the Budapest Memorandum. First, Ukraine never possessed independent nuclear capability: the warheads were Soviet, and all command-and-control systems, including launch codes, remained in Moscow. Ukraine had the hardware but not the ability to use it. Second, the Budapest Memorandum was a political commitment rather than a legally enforceable treaty, since it lacked any enforcement mechanism. Like all political commitments, it was a product of circumstance and expectations. The circumstance was Russia’s geopolitical collapse in the 1990s. The expectation was that independent Ukraine would remain within the post-Soviet space. (Ukraine was a founding member of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), though it never ratified its participation.)

Russia’s expectations were grounded in the political assurances of Ukraine’s own leaders. Ukraine’s President Leonid Kuchma, who signed the Budapest Memorandum, repeatedly affirmed Ukraine’s non-aligned status, its intention to remain militarily neutral, and its commitment to continued cooperation with Russia through various CIS institutions. Throughout the decade, Ukrainian leaders publicly stated that NATO membership was not under consideration, while Ukraine’s economy and defence industries remained deeply intertwined with Russia. Although none of this was codified in the Memorandum, Russia treated it as the political context underpinning the 1994 settlement—an understanding it believes was overturned by the 2008 Bucharest Declaration (“Ukraine will become a member of NATO”) and Ukraine’s 2019 constitutional amendment which made NATO and EU memberships “irreversible” objectives of policy.

So yes, Russia broke a political commitment—but one which depended on a broken Ukrainian commitment.

3. The sanctity of borders

It has become a cardinal principle of our “rules-based order” that international frontiers are sacrosanct, even if they have been arbitrarily created (as was true of most states in the Middle East), or if the circumstances under which they were created have changed. Today’s Ukraine is the result of a continuous reshaping of frontiers.

In Imperial Russia, there was no political or administrative entity called Ukraine: “Ukraine” was a generic name for frontier territory. Territories now in Ukraine were fragmented into several subdivisions, and Ukrainians were scattered around these administrative units with no strong sense of a separate identity as Ukrainians.

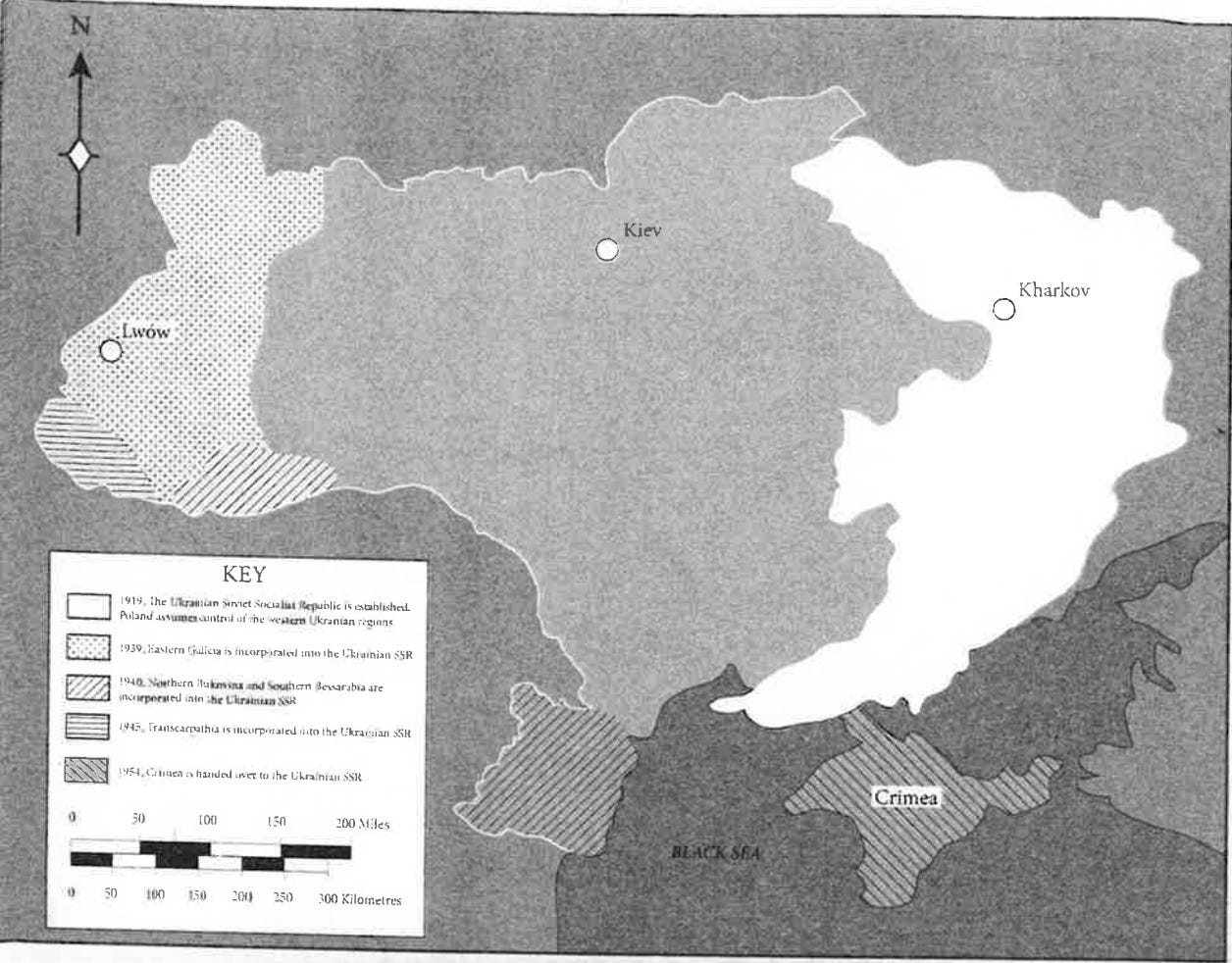

In 1922 Ukraine became a founding member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In principle all these republics were sovereign, but in fact ruled by the Communist Party headquartered in Moscow. In 1939 East Galicia (centred on Lwów and formally recognised as part of Poland in 1923) was incorporated into Soviet Ukraine as a result of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. In 1940 northern Bukovina and southern Bessarabia were added, again as agreed with Nazi Germany. In 1945 Transcarpathia was annexed to Ukraine as a result of the Soviet victory over Germany. In 1954, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev handed Crimea to the Ukrainian republic.

MAPS OF CHANGING UKRAINIAN FRONTIERS:

The problem revealed by this history is that when, for one reason or another, existing frontiers no longer fit reality, there is no peaceful international mechanism for changing them (as opposed to securing an internally agreed change in borders, such as the creation of two states—the Czech Republic and Slovakia—out of the single state of Czechoslovakia in 1993). Modern Ukraine is a creation of frontiers first fixed by an agreement between two dictators (Hitler and Stalin) and later ratified by the victorious Allies on the principle of uti possidetis juris (“as you possess, so you shall possess”). A major difficulty in making peace in Ukraine today is that neither Ukraine nor Russia in fact possesses all the territories they claim to possess.

4. Spheres of influence and the Monroe Doctrine

The principle of the inviolability of frontiers is closely allied with the principle of equal sovereignty—i.e. each state is free to choose whatever foreign or domestic policy it likes. This implies the rejection of such old-fashioned ideas as buffers, spheres of influence, or externally enforced neutrality.

In my post of 1 December, I mentioned that America had never officially repudiated the Monroe Doctrine. I did not yet know that the Trump administration was about to restate it in its 2025 National Security Strategy, published on 4 December. This startling document deserves a separate post of its own. Its relevance to the Ukraine crisis is that it breaks with the USA’s hitherto unquestioned strategic priority of defending Western Europe against Russian aggression; indeed, it accuses European “elites” of “hysterical” over-reaction to the supposed Russian threat. It also marks a break from the liberal project of regime change to make the world safe for democracy. Paradoxically, the only regime changes it favours are the displacement of European elites by populist movements.

The “Trump Corollary,” dated 5 December, amounts to an emphatic reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine. The American people, not “foreign nations nor globalist institutions,” must be masters in their own hemisphere, and cannot allow this mastery to be challenged by external powers. Its relevance to our argument is that if Washington reserves the right to police its own strategic periphery, it becomes harder to dismiss out of hand Moscow’s claim that NATO’s eastward expansion violated de facto acceptance of spheres of influence in the post-Cold War settlement.

5. Military Keynesianism

The rearmament momentum in Europe has drivers that extend well beyond the stated security rationale of countering Russia. A growing strand of European policy thinking suggests that the rearmament drive serves a second, less openly acknowledged purpose. As Berg and Meyers (CER, 2025) argue, much of the EU’s rearmament agenda is being justified through the language of security, yet in practice functions as an attempt to revive Europe’s weak productivity and failing industrial base—an industrial strategy masquerading as a defence imperative, in effect a post-pandemic and post-stagnation strategy of military Keynesianism. From this perspective, the insistence on an existential Russian threat functions not simply as a strategic assessment but as political cover for a massive industrial mobilisation that EU leaders hope will restore European economic competitiveness.

I agree that Europe needs new sources of growth, but the attempt to smuggle industrial policy in under the banner of a war footing—by cultivating fear and exaggerating threats—is neither honest nor acceptable. Manufacturing a warlike mindset to legitimise economic renewal may be politically convenient, but it corrodes democratic debate and risks locking Europe into a perpetual militarisation that has little to do with Europe’s real economic challenges.